It’s a scary time.

International law? Unenforceable. Convicted felon for president? Probable. Rollback of women’s rights? Happening.

As fascism bares its teeth, we must not take for granted the freedoms we’ve gained. They can be lost in one election.

Those are my thoughts as I listen on repeat to this beautiful song by Mari Boine. I feel my heart slow. It is good medicine for those of us with a mother wound, recent or ancient, which is, I suppose, all of us.

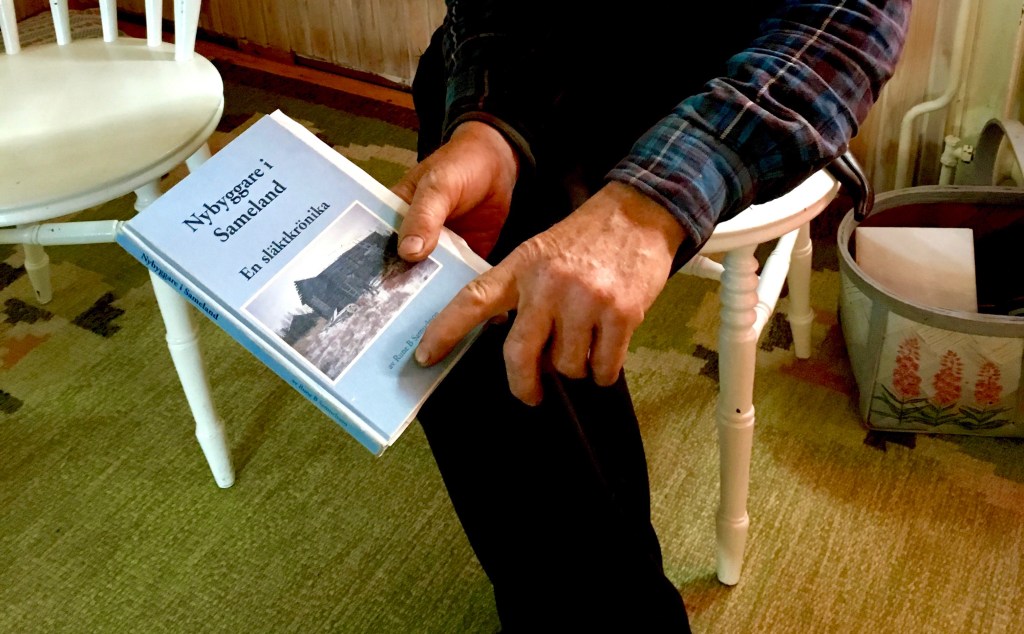

In the introduction (below), Mari explains that her mother was a Laestadian Christian. For those yet unfamiliar, the faith is named for its 19th century Swedish Sámi founder, Lars Levi Laestadius, who finally succeeded in Christianizing the Sámi, or so it is said, after hundreds of years of failed missions. But it was not so simple.

Long before “woke” meant “aware of historical oppressions,” Laestadians referred to themselves as “the awakened”: aware of an embodied, transformative experience of the Divine not available through performative religion. Colonial power dynamics remained, however, shifting from male priests to male lay preachers, while principles like simplicity and moderation hardened into performative taboos. My own Laestadian mother, who died in 2021, never wore makeup or jewelry (other than a wedding band), never had her hair cut or styled, never saw a film, concert, or ball game, never played an instrument, never tasted wine, never heard a woman preach, never had her own bank account. Married at 17, she had nine children, and when her daughters chose different paths, she was profoundly hurt. I l often wished that I could free her, like a bird from a cage, and I suspect she felt the same about her mom, whose life was even more restricted.

Would Mari’s mom have attended her concerts had she been able to do so in disguise, without her Laestadian community punishing her for it?

Perhaps, in a way, she is at every performance, as transported as the rest of the audience, free to be carried away by beauty. It’s a lovely thought, and while I’m at it, I’ll place my mom, her distant relative, alongside, smiling and swaying.

Bravi tutti, Mari Boine and band, Knut Bry for the videography, Vojta Drnek for the editing, and Outi Pieski for the amazing art. Great work. (I am chuffed that my translation is captioned.)

Introduction

Mu eadni / Mother of Mine is a song of love and lament for the woman who gave me life, and for all women who suffer under systems that shame and subordinate them. As a Laestadian Christian, my eadni was bound by strict gender roles, and that insidious association of the feminine with sin. She was taught to be self-denying: that her highest purpose as a woman was obedience. (To males, naturally, all the way down.)

When her daughters resisted, she felt it was a personal failure. And yet, she was Sáami, with echoes and stirrings from a much older worldview, one that celebrated the feminine, that found purpose in reciprocity, not hierarchies. Sometimes, I feel her with us, free from shame, sharing our freedom. Smoothing our fringe. Adjusting our belts. Asking us to twirl.

Mari Boine

Mu Eadni

You were not permitted to preen

Not for you the silken liidni

Nor were you allowed to dream

Of glamour, or vainglorious gákti

Feminine desire you had to condemn

You could not defend even your own daughters

For pleasures of the flesh

Could open the soul to sin

O mother of mine, mother of mine

If I could draw you close again

I would swathe you in silk and pearls

Ribbon you in silver and gold

Adorn you and adore you

So we three daughters, free

Could recall you to unshamed joy

You were not permitted to preen

For pleasures of the flesh

Could open the soul to sin

My mother, O my mother

Our mother, O our mother